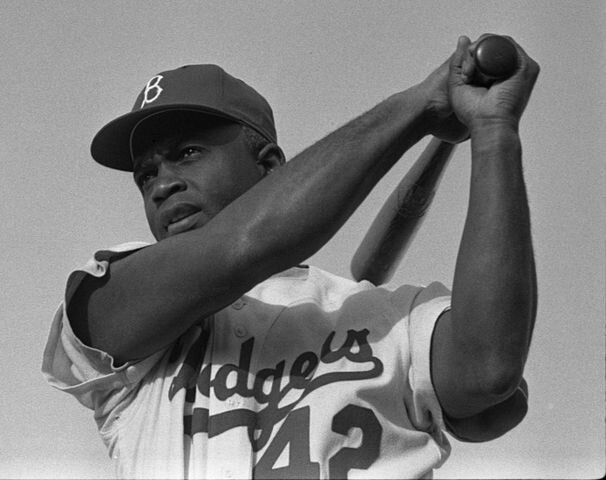

A Jackie Robinson Day Without Baseball

Were they playing baseball games today, which sadly they are not, today would have been Major League Baseball’s annual Jackie Robinson Day, when every player on every team wears number 42 in honor of the man who broke baseball’s color barrier. I have been fascinated by the life of Jackie Robinson since I was a kid when I read a biography about him from the library. (Go reading! Go libraries! Go books!)

The Robinson story has always gripped me for a number of reasons, but if I just boil it down to one it would probably be how incomprehensible his journey was to a little white kid growing up in west Texas. There are certain things which are just hard to wrap your brain around, and Jackie Robinson’s accomplishments, both on the field and off of it, are close to the stuff of legend.

He was a very good athlete, and without the weight of breaking the color barrier he could have been even better. Every day of his life who he was carried more weight than I can possibly imagine. Yet, if anything, I think Jackie Robinson has been underrated by history. This may seem odd to say of someone as historically significant as Jackie Robinson, but let me explain myself. Consider this quote from Cornell West, “More even than either Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, or Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights movement, Jackie Robinson graphically symbolized and personified the challenge to the vicious legacy and ideology of white supremacy in American history.” (1)

When Cornell West says that Robinson symbolized the struggle for civil rights even more than Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr. we should take notice. It is probably easy to look at Robinson and relegate his achievements to the baseball diamond. To say that he broke the color barrier in baseball, and really to mean, perhaps unintentionally, only baseball.

But what if the grand scheme of Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey had failed? What if breaking the color barrier had been a colossal bomb? Rickey knew the stakes, and that is why he chose the man he did. In one of the great conversations of historical import between two men, Rickey and Robinson—both strong believers in Christ—hashed out a plan that was as much theological as it was social and athletic. Rickey put it bluntly to Robinson that he needed a man who had “guts enough not to fight back.” After a back and forth, the two men agreed on just what not fighting back and turning the cheek meant, and I think Jonathan Eig makes a compelling case that this has been misunderstood.

The story of the meeting between Rickey and Robinson has been told in countless media, passed down through the generations, shined up and smoothed over so that it has become one of America’s great fables. But in one important way, the accounts are often misleading. Rickey didn’t choose Robinson for his ability to turn the other cheek. Had Rickey wanted a pacifist, he might have selected any one of half a dozen men with milder constitutions than Jack Roosevelt Robinson’s. Rickey wanted an angry black man. He wanted someone big enough and strong enough to intimidate, and someone intelligent enough to understand the historic nature of his role. Perhaps he even wanted a dark-skinned man whose presence would be more strongly felt, more plainly obvious, although on this point Rickey was uncharacteristically silent. Clearly, the Dodger boss sought a man who would not just raise the issue of equal rights but would press it. It is testament to Rickey’s sophistication and foresight that he chose a ballplayer who would become a symbol of strength rather than assimilation. It is testament to Robinson’s intelligence and ambition that he recognized the importance of turning the other cheek and yet found a way to do it without appearing the least bit weak. (2)

Eig’s understanding here is insightful. The Jackie Robinson of 1947 was not the Jackie Robinson of 1951 or 1954. Turning the other cheek looked different as more African Americans entered the game, and Jackie’s own character and determination made the realization that change was happening, ready or not, inescapable.

In the later years of his life Robinson became more controversial as the world became more complicated. He clashed with Malcolm X, openly supported Richard Nixon, and he struggled to deal with an America whose dream always seemed to stay just out of reach for a person of color, even for the great Jackie Robinson.

Near the end of his far too short life Jackie Robinson write his autobiography, I Never Had It Made. At the end of the preface he reflected on his first World Series game and had this to say, “As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.” (3)

There’s no baseball today, but it would be good to remember Jackie Robinson anyway. To remember the Robinson of 1919, the Robinson of 1947, and the Robinson of 1972. To remember that it’s 2020, and we’ve still got work to do.

(1) Robinson, Jackie. I Never Had It Made . Ecco. Kindle Edition.

(2) Eig, Jonathan (2007-03-20). Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson's First Season (Kindle Locations 196-199, 588-600). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

(3) Robinson, Jackie. I Never Had It Made . Ecco. Kindle Edition.